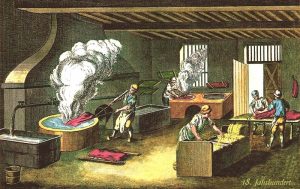

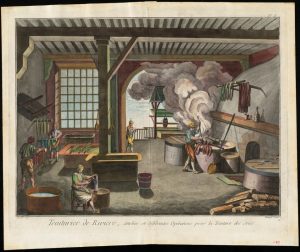

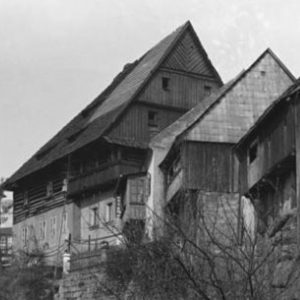

In historical sources, the building is referred to as a woad dyer’s house. A woad dyer applied dark-coloured dyes (such as blacks, browns, or blues) to wool and woollen fabrics. Yarn or fabrics were dyed in a hot dye-bath, which is why a fire had to be maintained underneath the vats.

The preserved heating chamber is made of sandstone blocks and was once surrounded by dyeing vats placed in a brick lining. The vats fell victim to the ravages of time, however, and only the brick lining survived. In its prime, the heating chamber had six or seven vats in total. The attendant would climb down into the chamber where it was possible to feed and tend to the fire. Smoke would billow out from under the vats and back into the chamber above the attendant’s head, leaving through a wide chimney that was later gutted. The chamber is held together from the outside by a wooden bond beam. A dendrochronological analysis (tree-ring dating) of the beam established that the tree used to make it was cut down in 1690. It is, thus, most likely the oldest piece of wood in the entire building.

A wooden drum — the dyer’s reel — was placed over the hot dye-bath while the fabric was reeled in and out to ensure proper dyeing.

The dyed cloth was wrung out over a vat and then most likely hung up in the attic of the adjacent house to dry, which is why the ceiling was so unusually high.

Following the decline of cloth weaving, the workshop switched to indigo dyeing and cotton and linen fabrics were dyed in a cold indigo solution. After the fabrics were dry, they had to be ironed using a mangle and an ironing press. An indigo vessel from this period as well as the remains of a huge mangle have been discovered.